Philip Crim

12-14-2022

The American hornbeam (Carpinus caroliniana Walter) is very common across much of Eastern North America, preferring wetland margins and floodplains from the Atlantic coast to the Great Plains. With such a large native range, the species has accumulated a large number of common names such as the most widely-used “hornbeam” as well as “musclewood” due to the smooth, fluted nature of the trunks and “blue-beech” referring to the smooth, sometimes silvery-blue color that is similar to some American beech trees. The latter name I hear very frequently in CNY and was always the name we used for it around the farm when I was a child.

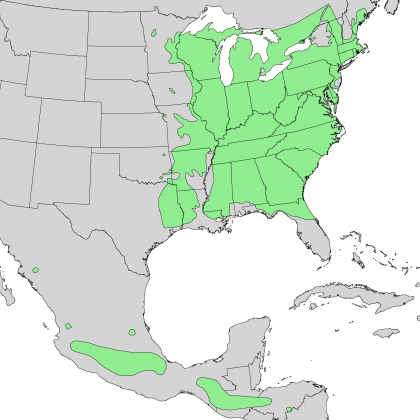

The wide native range of American hornbeam has not only led to many common names, but also to a large amount of genetic and morphological variation. These differences seem to be fairly consistent within two main groups, currently classified as subspecies: a roughly northern subspecies, and a generally more southern subspecies that is typical of the coastal plain from Long Island south. Following this classification, our local CNY hornbeams are actually Carpinus caroliniana ssp. virginiana (Marshall) Furlow.

The differences between the northern and southern types have been studied in detail, and a range of intermediate plants can be found in the transition zone where the two groups meet. In a nutshell, the northern type bears distinctive dark glands on the bottoms of the leaves, while the southern populations lack these and have smaller leaves with more acute tips. These differences can be very subtle, and there are some serious questions about whether they represent meaningful genetic differences between populations assigned to one or the other. To my knowledge, there is currently no study examining population genetics of this species across its native range, and in my opinion these groups probably merit no more than the status of a botanical variety— a good step down from recognizing them as subspecies. While they may represent fairly distinct and morphologically uniform lineages that are on their way to being their own species, they are likely very early in this process.

While we may have only one species of hornbeam in the United States, there is a bit more variation south of the border. If you look at the range map above, note the populations that are present in Mexico and Central America. These have been variously described as falling under the variation of American hornbeam or as varieties (Carpinus caroliniana var. mexicana; var. tropicalis) or even as a separate species. At present, the prevailing view seems to recognize C. tropicalis as distinct and encompassing two forms: the main subspecies, and ssp. mexicana; I’m not entirely sure if these plants have been studied well enough to justify this treatment, however. Hornbeams are much more diverse in Eurasia, and the genus as a whole is split into two main groups: Section Carpinus including our native species, and Section Distegocarpus in Asia. The latter is rarely seen in North America, and some species have unusual features such as flaky and furrowed bark. Indeed, genetic studies have shown that some species in that group are more closely related to the hophornbeams (Ostrya) than to other Carpinus species, a situation which will someday force a reclassification (and likely combination) of these two groups.

In nature, our native hornbeam tends to be an understory species in areas with moist soil. Riparian margins and floodplains tend to suit it very well. In cultivation it is a tough and durable species, able to withstand compacted soil and a wide range of soil pH conditions. It’s also an excellent option for restoration and naturalization, as it is an important source of browse for many caterpillars, mammals, and the nutritious nutlets within the fruits are sought after by game birds. In terms of popularity as an ornamental, American hornbeam comes up short versus the European hornbeam; a species that has been cultivated for millennia and which offers a range of different cultivars with exceptional ornamental traits.

European hornbeam is often seen in cultivation as an upright, fastigiate street tree. In fact, I cannot recall seeing it as anything but that, except in an arboretum. It is likely even more durable in cultivation to human sources of abuse than our native species, which is a valuable trait for any street tree. The formal appearance of cultivars that have been selected for a tidy, upright growth habit makes it a valuable addition to the palette of urban street trees. In addition, there is little evidence that it poses a risk as an invasive species.

Our native hornbeam has many excellent qualities, but until recently there have been few selections taking advantage of these traits. A big potential advantage is in the fall color department; although the species is quite variable in terms of fall color, some individuals have exceptional scarlet fall tones, or a mix of yellow, orange, and red. However, this is a highly variable trait, and I have seen some individuals turn black before dropping their leaves; not exactly an appealing quality for horticulture. Against the American plants with excellent fall color, the European species is often a subdued shade of yellow and cannot compete. Recently, at least one hybrid purporting to combine the tidy growth habit of European selections with improved fall color from the American species has started hitting the market. Overall, this is the latest in a sea change for this species, which is seeing more horticulturalists adopting and promoting our American hornbeam and using it as a source of genetics for breeding.

Limeledge will host a species collection of Carpinus and begin scattering some of the interesting new cultivar selections across the grounds as well. One of our first plantings was a Japanese hornbeam, a Section Distegocarpus species with spectacular foliage. We will also be one of the few collections to showcase both the Northern and Southern types of our familiar and beloved hornbeam. One very intriguing selection we have is a weeping clone called ‘Stowe Cascade’ that was discovered at Stowe Botanical Gardens in North Carolina. Interestingly, the original tree was found in the transition zone between the northern and southern forms, and it appears to be an intermediate. While it is certainly not as well-tested as some of the weeping European selections, we are very excited to watch it develop at Limeledge and perhaps try our hand at a bit of hornbeam breeding of our own. We also have a variegated selection discovered by Philip Crim near Albany, NY that emerges in spring with bright gold speckles that age to a snowy white on green and lingers throughout the growing. The future is bright for our native blue-beech… I mean hornbeam!